Jun 4 2015

A year ago, when her son Bobby, now 10, was first diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Jamie Lee wasn’t surprised. “By age 2, he didn’t crawl,” she recalls. “And there were other developmental issues.”

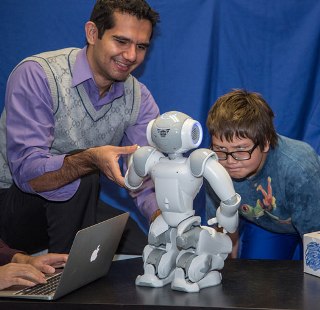

An interdisciplinary faculty-student-robot research team based out of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science is conducting a pilot study exploring whether humanoid robots like NAO can improve social and communication skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Photo: Wayne Armstrong

An interdisciplinary faculty-student-robot research team based out of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science is conducting a pilot study exploring whether humanoid robots like NAO can improve social and communication skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Photo: Wayne Armstrong

Although she wasn’t taken aback by the diagnosis, she was daunted by the parenting hurdles sure to lie ahead. After all, children with ASD not only learn differently than their neurotypical counterparts, they tend to struggle socially. When it’s customary to make eye contact, they often gaze elsewhere. When a smile would be appropriate, they may deliver a scowl. And when a playmate communicates frustration via a facial expression, autistic children often don’t recognize the signal, responding with behavior that makes matters worse.

Although Bobby has been far more socially successful than many children with ASD, he still faces challenges. “He has a few close friends, but not a lot,” Lee says. “He doesn’t necessarily connect with a lot of his peers.”

But Bobby does connect with a personable playmate named NAO, the remote-controlled star of an interdisciplinary faculty-student-robot research team based out of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science. Led by Mohammad Mahoor, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, the team is conducting a pilot study exploring whether humanoid robots like NAO can improve social and communication skills in children with ASD.

“You may ask, why a robot? Why not a human?” Mahoor says. “Humans are very overwhelming for kids with autism.”

Toys with technology, on the other hand, are downright accessible. As team member and psychology major Sophia Silver notes, “A lot of kids on the spectrum like mechanical things.”

And with the 23-inch-tall NAO, there’s plenty to like. “He can walk, talk and dance,” Mahoor says. He can also direct autistic children in a host of activities designed to improve their recognition of facial expressions and to help them cast their gaze appropriately. Using his four microphones and two cameras, NAO not only plays with the kids, he records essential data about each study participant — everything from the duration and frequency of their direct gazes to the range of their facial expressions. And when the kids succeed, NAO can even enlist them in a celebratory high-five.

For autistic kids, these accomplishments are something to celebrate. As Mahoor notes, “These are the bases of human sociability.”

For his part, Bobby considers NAO an approachable playmate with a delightful gift of gab. “He asks a lot of questions; he talks back,” Bobby says of NAO. “I kind of like it.”

What’s more, his 9-year-old brother, Jorian, who often comes along for Bobby’s dates with NAO, is a fan, too. The robot gives the brothers a common interest, in addition to animals and dinosaurs. (“I’ve been really interested in robots since the first grade,” Jorian explains.)

“They’ve been just ecstatic [about playing with NAO],” Lee says of her sons. “They’re boys, and they like to push buttons. Anything that moves and isn’t quite human fascinates them.”

The autism/robot project is one of several research initiatives led by Mahoor, an expert in visual pattern recognition, social robot design and bioengineering. With this project, he aims to build on studies pointing to the therapeutic potential of robots for the ASD population.

To date, Mahoor’s study has enlisted 24 participants, ages 7 to 17, who, over the course of six months, come to a University experiment room every two weeks for 30-minute sessions with NAO. Mahoor hopes to work with up to 50 children with high-functioning autism in this two-year study, scheduled to conclude in another year — if he can find the funding to sustain the project.

Made by Aldebaran Robotics of France, NAO is programmed, scripted and operated by members of the DU research team. Huanghao Feng, a graduate student in computer engineering, has been with the project from the beginning. Initially, he joined the team to learn more about the newfangled NAO, but the project has also taught him a lot about working with autistic children. When they don’t respond to the robot or when their attention wavers, he repeats the robot’s requests or helps them stay on task.

One of the activities incorporates a handful of small beanbags, each sporting a photo of a person demonstrating an expression — happiness, perhaps, or sadness or anger. The child is asked to find, and show NAO, the toy with the angry face, or the happy face. This exercise helps participants identify the emotions attached to facial expressions — a skill, Silver says, that will serve them well.

“If kids can’t identify that another child is angry, they’ll get in more fights. They’ll have trouble making friends,” she explains.

Other exercises, Mahoor notes, work on what is known as joint attention — in other words, shared focus on an object. NAO may, for example, ask the child to follow his gaze to, say, a line of boxes. “I have kids who are able to follow what NAO asks them to do. ‘Look at that object or pick up that object.’ Then NAO gives them a hug or a candy, a reward,” Mahoor says.

These moments of triumph are captured on NAO’s microphones and cameras, as are the duration of direct gazes and the frequency of gaze shifts. “After the sessions,” Feng says, “I go back to the lab and process all the data.”

Preliminary findings suggest that NAO is helping some of the children maintain a direct gaze for longer periods. The robot also is helping some parents better understand their child’s developmental progress. For example, Bobby’s experiences with NAO have helped Lee learn about his social awareness and social skills. “It verified that he is very high-functioning,” she explains.

Bobby’s interactions with NAO also empowered her to educate his teachers about his abilities and to direct his therapist toward his bigger challenges. “It really gave me the confidence to tell the therapist we’re working with, ‘No, we don’t need to work on that. We need to work on this.’”

Robots bring another advantage to a research team intent on repeating exercises and measuring data over time, Mahoor says. Robot interactions can be conducted precisely the same way again and again. That simply wouldn’t be possible with a human, who might introduce a new variable into a game or conversation.

It’s too soon to know just how effective robots can be. Not every child engages with them, but Feng and Silver have witnessed significant progress in several children.

Take the case of one nonverbal little boy. “At the beginning,” Feng says, “he was completely scared of the robot. But after several sessions, he hugged the robot and kissed the robot. He even came up and hugged me.”

Silver takes equal pleasure in such developments. “To see them excited about something is fun,” she says. “And it is really liberating for their parents as well.”