Sep 22 2014

It is where we all came from and it is vital to our future, but the earth’s oceans, seas and waterways remain a mystery to us – a final frontier. The Sunrise project is at the forefront of a revolution in communications, creating an underwater ‘internet of things’, that will mobilise robots to work in groups, interacting together and passing back information to us on life underwater.

SUNRISE_(c)_Marco_Merola

SUNRISE_(c)_Marco_Merola

The internet is omnipresent and has become a part of how we live, but now this connectivity is being extended from where we all take it for granted to where it has never been before – underwater.

Thanks to the SUNRISE project, supported by the European Commission under the 7th Framework Programme , underwater robots will be able to work autonomously, having received instructions. For the first time they will be able to communicate to each other and send data back to computers through the Internet, regardless of swiftly changing circumstances and challenges to data transmission.

‘The gaps in our knowledge of the underwater world are extensive. We know so little despite the fact that marine ecosystems are central to the health of our planet and vital to our economies,’ project leader Dr Chiara Petrioli says. Identifying threats to oil and gas pipelines, monitoring the environment, protecting archeological sites and finding out more about the geology of our planet – the ways teams of aquatic robots could help us learn more is endless, ‘This list is as extensive as your imagination,’ says Dr Petrioli.

Designing robots which can communicate in rapidly changing environments

Those changing environments are one of the key challenges the project faces. The robots communicate to each other using acoustic signaling, as do marine mammals. But whereas a dolphin will adapt the way it signals according to what is around it, robots need to be programmed to do so, presenting researchers with the task of developing machines capable of responding to a rapidly shifting set of variables. ‘Salinity, temperature, interference in the form of waves or passing shipping, all these will change the range of effective communication,’ explains Dr. Petrioli. This unpredictable environment is one of the key ways the internet of things underwater differs from our land-based use of WiFi and the internet.

The need to respond reliably to the shifting environment means multiple robots are needed so if one can’t communicate temporarily, another will take over the signaling. Schools of robots will carry a greater number of sensors and cover a larger area, cooperating and communicating together. Those operating them will send messages through modems transmitting acoustic waves. The waves are modulated to send information – but bandwidth is limited meaning transmission rates are slow. Additionally, sound waves only travel 1 500 metres a second, five orders of magnitude slower than radio communication in the air. Only a relatively limited range of tone will travel well – high tones don’t go so far.

‘These challenges can only be met by bringing together a cutting-edge team with partners from Italy, Germany, Portugal, Netherlands, Turkey and United States . This is the biggest scale endeavor in this field, globally. We are putting Europe at the frontier of this type of work,’ says Dr Petrioli. The international dimension means that the project’s labs also include underwater zones as diverse as the Baltic and the Mediterranean, ‘We get to try our prototypes in environments that present completely different challenges, making for stringent testing.’

Results are starting to come in…

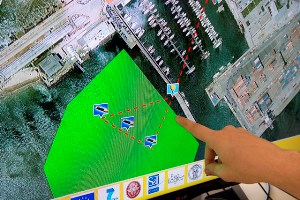

Work done in summer 2014, in Porto, showed the team that their ambitions were feasible: the components communicated, the robots responded to their instructions, the scientists were thrilled. On the practical side, they’ve already helped to find a lost container in the port of Porto. ‘The scientists are more enthusiastic than ever now we can see that we are on the right track,’ says Dr Petrioli.

Now that the project has working prototypes, the next stage is to bring in new partners from different areas of interest and set up centers off the coast of the USA, in Dutch lakes, and in the Black Sea in Turkey.