Apr 8 2014

It used to be that building and launching a working satellite was an enormously expensive and complex undertaking, feasible only for governmental and military agencies. But the CubeSat revolution of the past decade has placed satellite technology within reach of private companies, universities and even unaffiliated individuals. That revolution has been boosted by the existence of the International Space Station, which provides an additional launching platform enabled through regular commercial cargo flights.

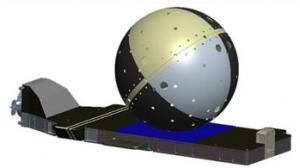

This is an illustration of Cyclops flight hardware with SpinSat satellite attached. Credit: NASA

This is an illustration of Cyclops flight hardware with SpinSat satellite attached. Credit: NASA

CubeSats are a class of research spacecraft called nanosatellites. The cube-shaped satellites measure about 4 inches on each side, have a volume of about 1 quart and weigh less than 3 pounds.

Putting the tiny satellites into orbit from the space station isn't as simple as shoving them out an airlock. It requires a special apparatus called a CubeSat deployer. This tool places a satellite into position to be grabbed by one of the space station's robotic arms, which places the CubeSat deployer into the correct position to release the miniature satellites into their proper orbits. At present, two CubeSat deployers operate aboard the station: the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) Small Satellite Orbital Deployer (J-SSOD) and the NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer. The upcoming launch of the SpaceX-4 commercial resupply mission, currently scheduled for August will enhance the space station's satellite deployment capabilities with the delivery of Cyclops. This tool, also known as the Space Station Integrated Kinetic Launcher for Orbital Payload Systems (SSIKLOPS), will provide still another means to release other small satellites from the orbiting outpost.

Daniel Newswander, an engineer with NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, said this addition will "fill out the quiver" of existing space station satellite deployment capabilities. The project is a joint effort of the International Space Station Program at Johnson and the Department of Defense's Space Test Program.

"Satellites come in all shapes and sizes," Newswander noted. "We were aware of several satellites that didn't really fit into the CubeSat launchers. We are deploying a spherical satellite as well as a cubic one that does not fit in the existing launchers. We are attempting to complement the other deployers that have been developed so that the [space station] has several deployment options to choose from. We are targeting satellites in the 50 to 100 kg [110 to 220 lb] class, especially those which geometrically do not fit in the existing launchers."

CubeSats have varied missions, and this year has been a particularly busy one for deployment of the satellites from the space station. Whether looking to help with imaging Earth for weather and ground data or advancing communications capabilities, the ability to set these satellites into orbit from the space station is the first step to enabling their missions. The resulting technology developments may contribute to advances in satellite technology for commercial use while enhancing Earth observation techniques.

Camille Alleyne, assistant space station program scientist, explained: "Because of the relatively low costs to build this technology, the demand for the CubeSat deployment capability has increased dramatically. Adding this third deployer as a space station facility allows us to meet demand and demonstrates the value of the unique platform for both space research and STEM education."

Cyclops will operate from the JEM and take advantage of the airlock's existing slide table. Newswander said, "The launcher will be stowed inside the [space station] for use whenever a satellite is ready to be deployed. Cyclops is placed onto the airlock slide table with the attached satellite and processed through to the external environment. Cyclops, with its attached satellite, is subsequently grasped by the robotic arm and taken to the deployment position. Cyclops then deploys the satellite and is returned to the airlock where it is processed back through and stowed internally for future utilization. Our design utilizes the Japanese robotic arm but does have the capability to use the [station's] main robotic arm if necessary."

It took Cyclops less than two years to launch. The space station program office approved the concept in October 2012, and the facility was ready for flight by spring of 2014. "It's been very rewarding, yet challenging at the same time," Newswander remarked. "You want to move as fast as you can because everyone's excited for the capability, but you need to ensure you do it right. So it's a continual tradeoff."

Newswander described one challenge: "how do you certify something in an environment that you can't replicate on Earth?" The answer is found in a great deal of engineering rigor, analysis, testing, safety assessments, verification and quality assurance. "You focus on applying the proper engineering and safety practices and processes to the design. We're trying to maximize the usable envelope available in the airlock, which is not something that anyone has really tried to do for satellite deployments. That, coupled with the challenges of satellite deployment from an orbiting space station really pushes your boundaries."

When it becomes operational later this year, the Cyclops deployer not only will add a permanent enhancement to the capabilities of the station, but perhaps it also will serve as a model for further technological innovation. "We built something that should be up there for the duration of the station," Newswander noted. "It is designed to accommodate several deployments a year, so we anticipate that it's going to be able to handle whatever need the [space station] community requires. We don't know if that will drive second generation designs; but, if someone comes forward in the future and takes an idea that we started off with and makes it better, we would welcome the enhanced capabilities. We consider the [space station] to be an invaluable resource not only to NASA but to the entire international community."