Performing autonomous scientific experiments is enabled by an artificial intelligence system—as many as 10,000 a day—possibly driving an extreme leap forward in the pace of breakthroughs in areas from medicine to agriculture to environmental science.

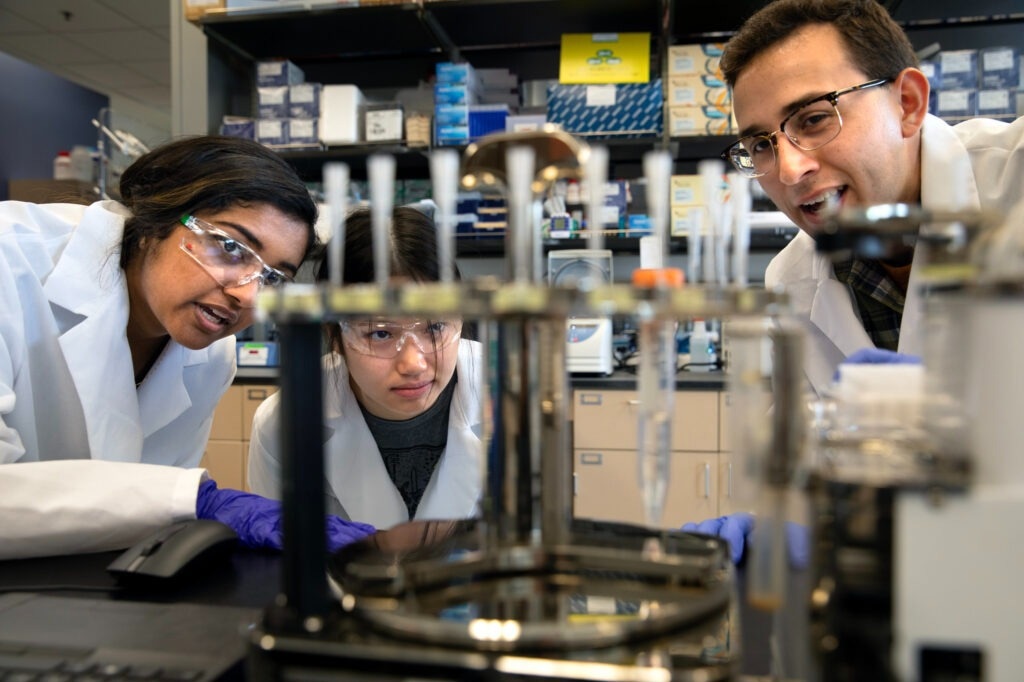

Paul Jensen, Assistant Professor at University of Michigan Biomedical Engineering and his graduate students have created an artificial intelligence agent that uses game-playing robots to answer scientific questions. BacterAI can assign autonomous scientific experiments for robots that eventually lead to answers that would normally take humans years to answer. Their Deep Phenotyping system has completed 931,038 automated experiments since January 2020. Image Credit: Marcin Szczepanski/Lead Multimedia Storyteller, Michigan Engineering

The research group was headed by a professor at the University of Michigan.

The study was reported in the Nature Microbiology journal.

That artificial intelligence platform, labeled BacterAI, mapped the metabolism of two microbes linked to oral health—having no baseline data to begin with.

Bacteria use up a few combinations of the 20 amino acids required to assist life, but each species needs particular nutrients to grow. The University of Michigan (U-M) group wished to know what amino acids are required by the microbes in humans’ mouths so they could promote their growth.

We know almost nothing about most of the bacteria that influence our health. Understanding how bacteria grow is the first step toward reengineering our microbiome.

Paul Jensen, Assistant Professor, Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan

Jensen was at the University of Illinois when the project began.

But, finding the combination of amino acids liked by bacteria is difficult. Those 20 amino acids yield over a million possible combinations, depending on if each amino acid is present or not. Still, BacterAI was able to find the amino acid needed for the growth of both Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii.

To determine the correct formula for every species, BacterAI tested hundreds of combinations of amino acids daily, sharpening its focus and altering combinations every morning based on the earlier day’s outcomes. Within nine days, it was producing precise predictions 90% of the time.

Dissimilar to traditional methods that feed labeled data sets into a machine-learning model, BacterAI made its data set via a series of experiments. By examining the outcomes of earlier trials, it emerges with anticipations of what new experiments may give the most data. Consequently, it found the majority of the rules for feeding bacteria with fewer than 4,000 experiments.

When a child learns to walk, they don’t just watch adults walk and then say ‘Ok, I got it,’ stand up, and start walking. They fumble around and do some trial and error first. We wanted our AI agent to take steps and fall down, to come up with its own ideas and make mistakes. Every day, it gets a little better, a little smarter.

Paul Jensen, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan

Little to no research has been performed on approximately 90% of bacteria, and the amount of time and resources required to learn even fundamental scientific information regarding them with the help of traditional methods is frightening. Automated experimentation could considerably expedite these discoveries. The research group ran up to 10,000 experiments in a single day.

However, the applications exceed microbiology. In any field, scientists can set up questions as problems for AI to solve via this kind of trial and error.

With the recent explosion of mainstream AI over the last several months, many people are uncertain about what it will bring in the future, both positive and negative. But to me, it’s very clear that focused applications of AI like our project will accelerate everyday research.

Adam Dama, Study Lead Author and Former Engineer, Jensen Lab, University of Michigan

The study was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health with assistance from NVIDIA.

Journal Reference

Adam, C., et al. (2023) BacterAI maps microbial metabolism without prior knowledge. Nature Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01376-0.