At the University of Michigan, a research group has come up with a new software tool to help scientists across the life sciences examine animal behaviors in a highly efficient manner.

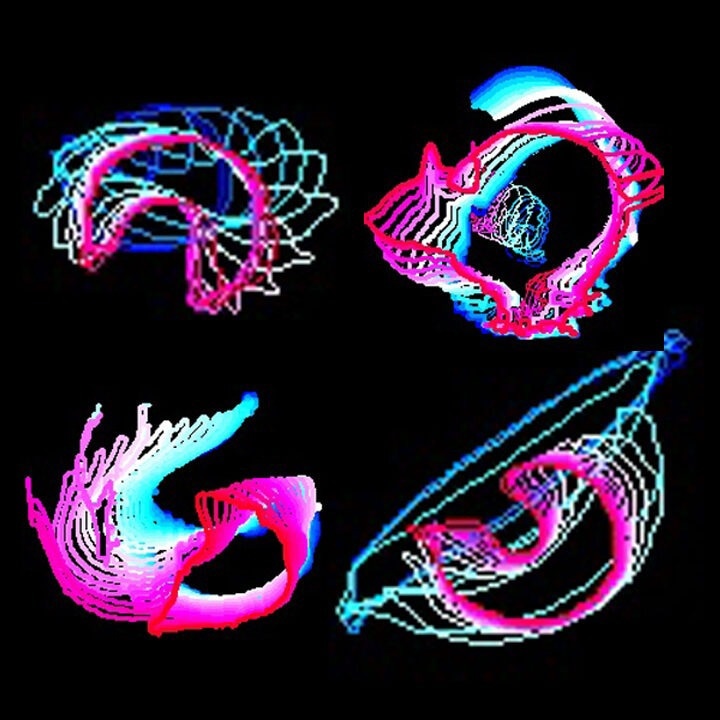

Pattern images merge outlines of an organism’s position at different timepoints to depict movement, providing a still image that increases LabGym’s accuracy in recognizing behavior types. Shown are the pattern images for mice (top right, bottom left) and Drosophila larvae (top left, bottom right). Image credit: Yujia Hu and Bing Ye, U-M Life Sciences Institute. Image Credit: University of Michigan

The open-source software, called LabGym, capitalizes on artificial intelligence to determine, classify, and count defined behaviors throughout several animal model systems.

It is important for researchers to quantify animal behaviors for a range of reasons, from comprehending all the ways a specific drug might impact an organism to mapping how circuits in the brain tend to communicate to create a specific behavior.

For instance, scientists in the laboratory of U-M faculty member Bing Ye examine behaviors and movements in Drosophila melanogaster—fruit flies—as a model to learn the functions and development of the nervous system. Since fruit flies and humans share several genes, these studies usually provide knowledge of human health and disease.

Behavior is a function of the brain. So analyzing animal behavior provides essential information about how the brain works and how it changes in response to disease.

Yujia Hu, Study Lead Author and Neuroscientist, Ye’s Lab, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan

The study was reported in the Cell Reports journal on February 24th, 2023.

However, determining and counting animal behaviors manually is tedious and highly subjective to the scientist who is making an attempt to analyze the behavior. Also, while some software programs exist to measure animal behaviors in an automatic manner, they come with difficulties.

Many of these behavior analysis programs are based on pre-set definitions of a behavior. If a Drosophila larva rolls 360 degrees, for example, some programs will count a roll. But why isn’t 270 degrees also a roll? Many programs don’t necessarily have the flexibility to count that, without the user knowing how to recode the program.

Bing Ye, Professor, Cell and Developmental Biology, Medical School, University of Michigan

Thinking More Like a Scientist

For these difficulties to be overcome, Hu and his colleagues made a decision to develop a new program that imitates human cognition—that “thinks” more like a researcher would—and is highly user-friendly for biologists who might not have expertise in coding.

With the help of LabGym, scientists could input examples of the behavior they wish to examine and teach the software what it must count. Further, the program makes use of deep learning to enhance its potential to identify and measure behavior.

One new aspect in LabGym that helps it employ this highly flexible cognition is making use of both video data and an alleged “pattern image” to enhance the reliability of the program. Researchers make use of videos of animals to examine their behavior. However, videos involve time series data that could turn out to be hard for AI programs to analyze.

Hu created a still image that displays the pattern of the animal’s movement by combining outlines of the animal’s position at various time points. This was done to help the program determine behaviors in a simpler way. The research group discovered that integrating the video data with the pattern images increased the precision of the program in identifying behavior types.

Also, LabGym is developed to ignore unrelated background information and take both the animal’s complete movement and the variations in position over space and time into account, just as a human researcher would. Also, the program could track multiple animals concurrently.

Species Flexibility Improves Utility

According to Ye, one more main feature of LabGym is its species flexibility. While it was designed with the help of Drosophila, it is not limited to any one species.

Ye stated, “That’s actually rare. It’s written for biologists, so they can adapt it to the species and the behavior they want to study without needing any programming skills or high-powered computing.”

As soon as she heard a presentation regarding the program’s early development, U-M pharmacologist Carrie Ferrario offered to help Ye and his group test and improve the program in the rodent model system she works with.

Ferrario, an associate professor of pharmacology and adjunct associate professor of psychology, studies the neural mechanisms that add up to addiction and obesity, using rats as models.

To finish the essential observation of drug-induced behaviors in the animals, she and her laboratory members had to depend hugely on hand-scoring, which is subjective and extremely laborious.

I’ve been trying to solve this problem since graduate school, and the technology just wasn’t there, in terms of artificial intelligence, deep learning, and computation. This program solved an existing problem for me, but it also has really broad utility. I see the potential for it to be useful in almost limitless conditions to analyze animal behavior.

Carrie Ferrario, Pharmacologist, University of Michigan

This study was financially supported by the National Institute of Health.

Besides Ye, Hu, and Ferrario, the study authors are Alexander Maitland, Rita Ionides, Anjesh Ghimire, Brendon Watson, Kenichi Iwasaki, Hope White, and Yitao Xi of the University of Michigan, and Jie Zhou of Northern Illinois University.

Journal Reference:

Hu, Y., et al. (2023) LabGym: Quantification of user-defined animal behaviors using learning-based holistic assessment. Cell Reports Methods. doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100415.