Jul 31 2019

Thunderstorms are widespread across the globe in summer. Besides ruining afternoons in the park, rain, lightning, and gusts of wind can destroy power grids and lead to electricity blackouts. It is easy to predict when a storm is approaching, but electricity companies want to be able to foretell which ones may destroy their infrastructure.

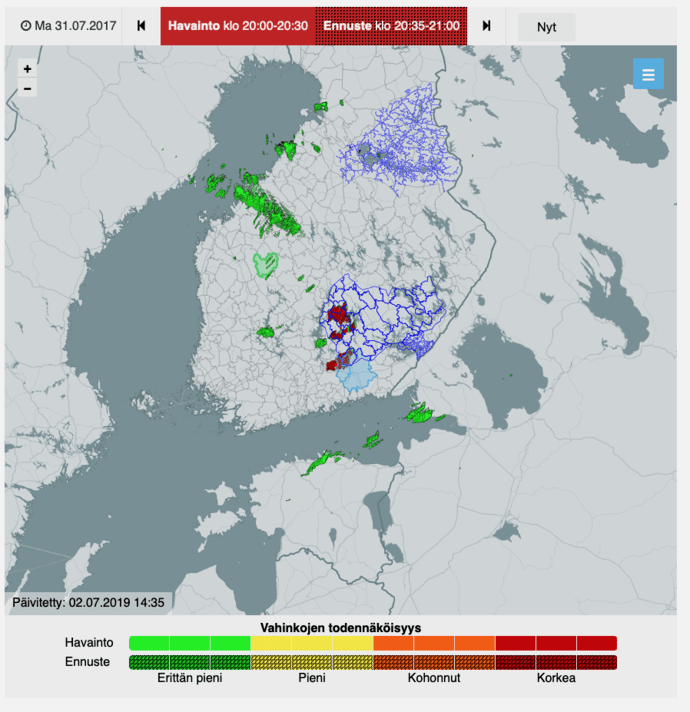

(Image credit: Aalto University)

(Image credit: Aalto University)

Machine learning—when computers detect patterns in available data which allow them to make predictions for new data—is suitable for forecasting which storms might result in blackouts. Roope Tervo, a software architect at the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) and PhD researcher at Aalto University in Professor Alex Jung’s research group has designed a machine learning method to forecast the severity of storms.

The primary step of teaching the computer how to classify the storms was by giving them data from power-outages. Three Finnish energy companies, Loiste Sähkoverkko, Järvi-Suomen Energia, and Imatra Seudun Sähkönsiirto, who have power grids throughout storm-prone central Finland, provided information regarding the number of power disturbances to their network. Storms were sorted into four classes.

A class 0 storm did not hinder electricity to any power transformers. A class 1 storm took down nearly 10% of transformers, a class 2 up to 50%, and a class 3 storm cut electricity to more than 50% of the transformers.

The following step was using the data from the storms that FMI had, and making it simple for the computer to comprehend.

We used a new object-based approach to preparing the data, which makes this work exciting. Storms are made up of many elements that can indicate how damaging they can be: surface area, wind speed, temperature, and pressure, to name a few. By grouping 16 different features of each storm, we were able to train the computer to recognize when storms will be damaging.

Roope Tervo, PhD Researcher, Aalto University

The results were encouraging: the algorithm was excellent at forecasting which storms would be a class 0 and cause zero damage, and which storms would be a minimum of class 3 and cause plenty of damage.

The scientists are integrating more data for storms into the model to help enhance the ability to distinguish class 1 and 2 storms from each other, and to make the prediction tools even more practical for the energy companies.

Our next step is to try and refine the model so it works for more weather than just summer storms, as we all know, there can be big storms in winter in Finland, but they work differently to summer storms so we need different methods to predict their potential damage.

Roope Tervo, PhD Researcher, Aalto University