Feb 1 2019

A new class of algorithms has become proficient at Atari video games 10 times faster than advanced AI, with an innovative approach to problem-solving.

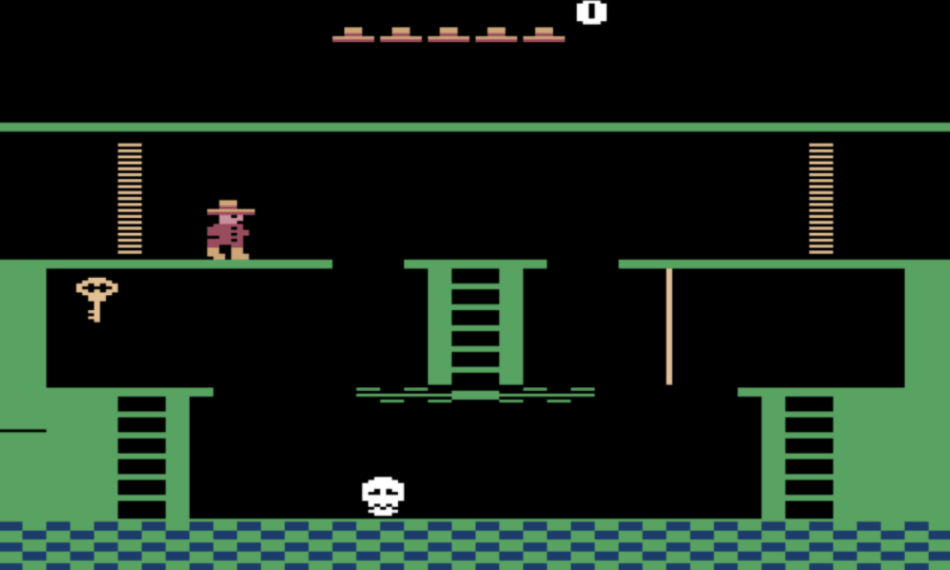

Scene from the first room in Montezuma’s Revenge. (Image credit: RMIT University)

Scene from the first room in Montezuma’s Revenge. (Image credit: RMIT University)

In a well-known 2015 research, Google DeepMind AI learned to play Atari video games like Video Pinball to human level, but infamously failed to learn a path to the first key in 1980s video game Montezuma’s Revenge because of the complexity of the game.

In the new technique formulated at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, computers programmed to independently play Montezuma’s Revenge learned from errors and identified sub-goals 10 times quicker than Google DeepMind to complete the game.

Associate Professor Fabio Zambetta from RMIT University reveals the new method at the 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence in the United States.

The technique, developed in partnership with RMIT’s Professor John Thangarajah and Michael Dann, incorporates “carrot-and-stick” reinforcement learning with an intrinsic motivation methodology that rewards the AI for being inquisitive and searching its environment.

Truly intelligent AI needs to be able to learn to complete tasks autonomously in ambiguous environments. We’ve shown that the right kind of algorithms can improve results using a smarter approach rather than purely brute forcing a problem end-to-end on very powerful computers. Our results show how much closer we’re getting to autonomous AI and could be a key line of inquiry if we want to keep making substantial progress in this field.

Fabio Zambetta, Associate Professor, RMIT University.

Zambetta’s technique rewards the system for independently investigating useful sub-goals such as “jump over that pit” or “climb that ladder”, which may not be evident to a computer, within the context of finishing a larger mission.

Human input is needed in other advanced systems to identify these sub-goals or else they decide what to perform next unsystematically.

“Not only did our algorithms autonomously identify relevant tasks roughly 10 times faster than Google DeepMind while playing Montezuma’s Revenge, they also exhibited relatively human-like behaviour while doing so,” Zambetta says.

“For example, before you can get to the second screen of the game you need to identify sub-tasks such as climbing ladders, jumping over an enemy and then finally picking up a key, roughly in that order.”

“This would eventually happen randomly after a huge amount of time but to happen so naturally in our testing shows some sort of intent.”

“This makes ours the first fully autonomous sub-goal-oriented agent to be truly competitive with state-of-the-art agents on these games.”

Zambetta said the system would function outside of video games in a broad range of tasks, when supplied with fresh visual inputs.

Creating an algorithm that can complete video games may sound trivial, but the fact we’ve designed one that can cope with ambiguity while choosing from an arbitrary number of possible actions is a critical advance. It means that, with time, this technology will be valuable to achieve goals in the real world, whether in self-driving cars or as useful robotic assistants with natural language recognition.

Fabio Zambetta, Associate Professor, RMIT University.