Dec 5 2017

Doctors-in-training will soon reach that day when they will be able to perfect specific medical practices on a robotic small intestine and also test medical treatments on a human-made device vs. animals.

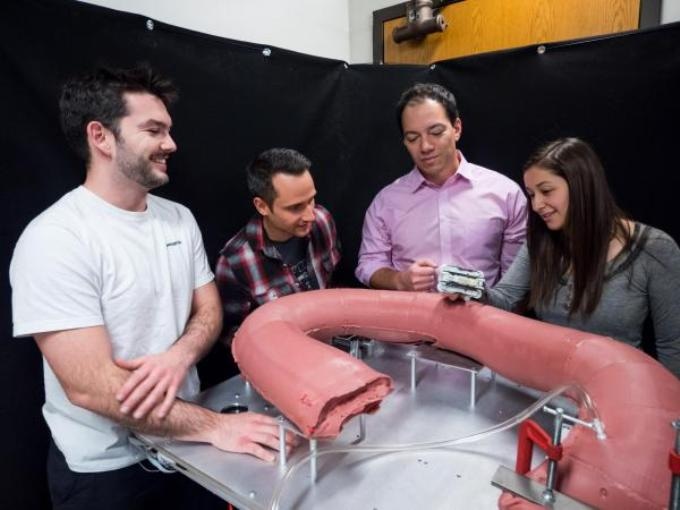

Mechanical engineering Associate Professor Mark Rentschler (far right) with graduate students (left to right) Levi Pearson, Greg Formosa and Micah Prendergast with an oversized version of a synthetic colon created as a senior design project. Rentschler is the lead scientist on a CU Boulder project to design a sophisticated robotic small intestine. Photo by Patrick Campbell, University of Colorado

Mechanical engineering Associate Professor Mark Rentschler (far right) with graduate students (left to right) Levi Pearson, Greg Formosa and Micah Prendergast with an oversized version of a synthetic colon created as a senior design project. Rentschler is the lead scientist on a CU Boulder project to design a sophisticated robotic small intestine. Photo by Patrick Campbell, University of Colorado

Mark Rentschler, mechanical engineering associate professor, is heading the effort to create an artificial, robotic small intestine for application in medical laboratories. The research is funded by a $1.25 million grant provided by the National Science Foundation.

While the small intestine is frequently assumed to be just a long coil of pink tubing within the abdomen, the truth is that it is a lot more complex. It is made up of ‘smooth muscle,’ a type of muscle capable of automatically functioning in the body. Think of the esophagus — when swallowing food, a range of smooth muscles expand and then contract one after the other in order to move the food from the mouth to the stomach. The small intestine functions in a similar manner, slowly advancing nutrients and food through the digestive tract.

Our goal is to make something that functions the same way, where we have a tube of synthetic muscles that can sense each other, so when one contracts, the muscle adjacent to it can feel that change and know it needs to contract next.

Mark Rentschler, Associate Professor, Mechanical Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder

The concept of a robotic small intestine may appear to be strange, since robotic devices are frequently thought of as being hard and rigid. However, Rentschler and an interdisciplinary team of CU Boulder researchers, including mechanical engineering Assistant Professor Christoph Keplinger, are now challenging that view.

People usually imagine robots as metallic and clunky, but we’re now developing softer materials and stretchable electronic circuits.

Christoph Keplinger, Assistant Professor, Mechanical Engineering

The team will obtain benefits from an emerging robotics technology Keplinger developed using a type of flexible, rubber-like material lined with sensors. It is also capable of expanding and contracting on demand.

Besides Rentschler and Keplinger, the research team also includes computer science Associate Professor Nikolaus Correll, mechanical engineering Associate Professor J. Sean Humbert and a number of undergraduate and graduate students.

Eventually, Rentschler visualizes the artificial small intestine as a tool for accelerating medical research and examination of new colorectal and colonoscopy cancer screening devices and treatments, and simultaneously reducing the use of testing on animals.

“Currently, this kind of work is often done with pigs, but their size is obviously not the same as humans, and they have some anatomical differences,” Rentschler says, “Being able to do testing with a robotic system that more closely matches human responses could help move things past animal testing and get to patients more quickly."

It would also be a powerful training tool. While many colonoscopies are carried out by gastroenterologists, they are also performed by general surgeons and primary care physicians. This system would provide doctors a new way to improve their skills before prior to treating patients.

The ability to develop a high-quality simulation is very attractive. It would offer all sorts of options that currently don’t exist.

Mark Rentschler