Jun 27 2016

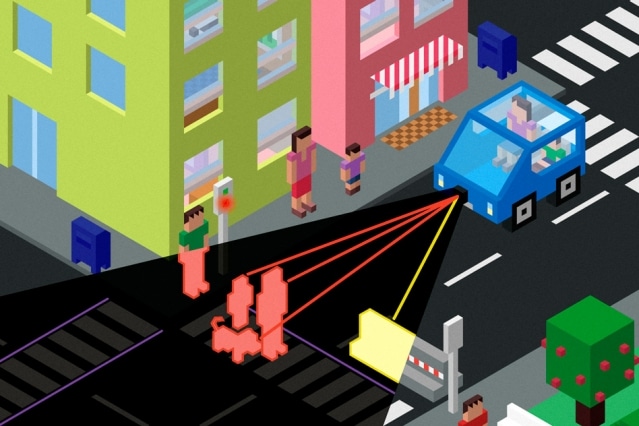

Driverless cars pose a quandary when it comes to safety. These autonomous vehicles are programmed with a set of safety rules, and it is not hard to construct a scenario in which those rules come into conflict with each other.

“Most people want to live in in a world where cars will minimize casualties,” says Iyad Rahwan, an associate professor in the MIT Media Lab and co-author of a new paper outlining the study. “But everybody wants their own car to protect them at all costs.”(Credit- Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

“Most people want to live in in a world where cars will minimize casualties,” says Iyad Rahwan, an associate professor in the MIT Media Lab and co-author of a new paper outlining the study. “But everybody wants their own car to protect them at all costs.”(Credit- Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Suppose a driverless car must either hit a pedestrian or swerve in such a way that it crashes and harms its passengers. What should it be instructed to do?

A newly published study co-authored by an MIT professor shows that the public is conflicted over such scenarios, taking a notably inconsistent approach to the safety of autonomous vehicles, should they become a reality on the roads.

In a series of surveys taken last year, the researchers found that people generally take a utilitarian approach to safety ethics: They would prefer autonomous vehicles to minimize casualties in situations of extreme danger. That would mean, say, having a car with one rider swerve off the road and crash to avoid a crowd of 10 pedestrians. At the same time, the survey’s respondents said, they would be much less likely to use a vehicle programmed that way.

Essentially, people want driverless cars that are as pedestrian-friendly as possible — except for the vehicles they would be riding in.

“Most people want to live in in a world where cars will minimize casualties,” says Iyad Rahwan, an associate professor in the MIT Media Lab and co-author of a new paper outlining the study. “But everybody wants their own car to protect them at all costs.”

The result is what the researchers call a “social dilemma,” in which people could end up making conditions less safe for everyone by acting in their own self-interest.

“If everybody does that, then we would end up in a tragedy … whereby the cars will not minimize casualties,” Rahwan adds.

Or, as the researchers write in the new paper, “For the time being, there seems to be no easy way to design algorithms that would reconcile moral values and personal self-interest.”

The paper, “The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles,” is being published today in the journal Science. The authors are Jean-Francois Bonnefon of the Toulouse School of Economics; Azim Shariff, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Oregon; and Rahwan, the AT&T Career Development Professor and an associate professor of media arts and sciences at the MIT Media Lab.

Survey says

The researchers conducted six surveys, using the online Mechanical Turk public-opinion tool, between June 2015 and November 2015.

The results consistently showed that people will take a utilitarian approach to the ethics of autonomous vehicles, one emphasizing the sheer number of lives that could be saved. For instance, 76 percent of respondents believe it is more moral for an autonomous vehicle, should such a circumstance arise, to sacrifice one passenger rather than 10 pedestrians.

But the surveys also revealed a lack of enthusiasm for buying or using a driverless car programmed to avoid pedestrians at the expense of its own passengers. One question asked respondents to rate the morality of an autonomous vehicle programmed to crash and kill its own passenger to save 10 pedestrians; the rating dropped by a third when respondents considered the possibility of riding in such a car.

Similarly, people were strongly opposed to the idea of the government regulating driverless cars to ensure they would be programmed with utilitarian principles. In the survey, respondents said they were only one-third as likely to purchase a vehicle regulated this way, as opposed to an unregulated vehicle, which could presumably be programmed in any fashion.

“This is a challenge that should be on the mind of carmakers and regulators alike,” the scholars write. Moreover, if autonomous vehicles actually turned out to be safer than regular cars, unease over the dilemmas of regulation “may paradoxically increase casualties by postponing the adoption of a safer technology.”

Empirically informed

The aggregate performance of autonomous vehicles on a mass scale is, of course, yet to be determined. For now, ethicists say the survey offers interesting and novel data in an area of emerging moral interest.

“I think the authors are definitely correct to describe this as a social dilemma,” says Joshua Greene, a professor of psychology at Harvard University, who has written a commentary on the research for Science, noting, “The critical feature of a social dilemma is a tension between self-interest and collective interest.” Greene adds that the researchers “clearly show that people have a deep ambivalence about this question.”

The researchers, for their part, acknowledge that public-opinion polling on this issue is at a very early stage, which means any current findings “are not guaranteed to persist,” as they write in the paper, if the landscape of driverless cars evolves.

Still, concludes Rahwan, “I think it was important to not just have a theoretical discussion of this, but to actually have an empirically informed discussion.”