Apr 13 2016

Simplifying the interactions between humans and robots could ensure a long-term presence of human beings in space. For instance, manned bases on Mars and the moon. At present, even basic robots appear to have impenetrable brains.

The space roboticist, Ricardo Bevilacqua, recently purchased an autonomous vacuum cleaner that wanders around the house on its own. The idea was to save some time to enjoy a few leisure activities, but instead of making the task easier, the robot only increased the tasks further. This is because the roboticist had to make sure that each and every room is robot-proof, and that doors are closed and cables and wires are not in the way. He even had to place electronic signposts so that the robot can follow the directions. However, Bevilacqua was unable to predict or understand what the robot would actually do. Therefore in order to play it safe, he started doing things to fit in the needs of the robot.

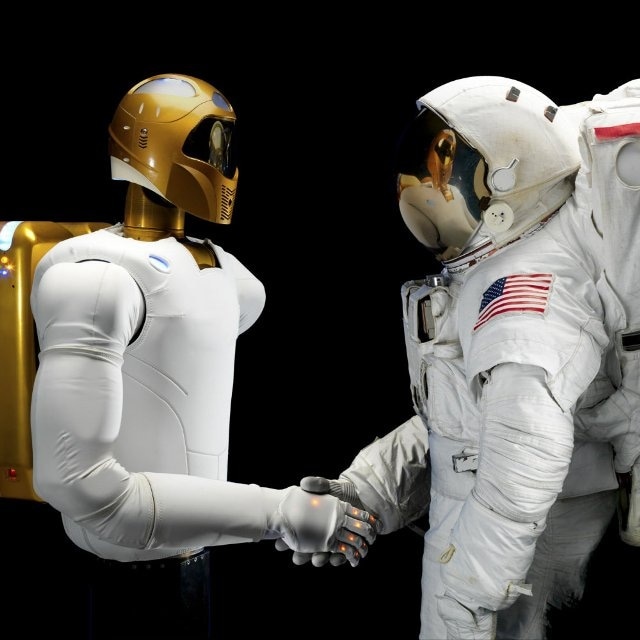

On a larger scale, Bevilacqua often thinks about these issues occurring in space. If an astronaut on a spacewalk is repairing or working on something that is damaged on the exterior of the spacecraft, he or she would require a number of tools and parts to replace or repair others. Here, an autonomous spacecraft could act as a floating toolbox, keeping the required tools and parts, and remaining close to the astronaut as he or she inspects the area that needs to be repaired. At the same time, another robot can clamp the parts together before they are fixed permanently.

However, there is no way of assuming that these robots would know where they had to go next, or to be useful and still remain out of the way. The astronaut would not know if the robots are intending to move to the very place he or she needs. If something comes loose suddenly, both the astronaut and the robot would not know how to stay out of each other’s way and still make sure that the situation is handled efficiently. Spatial orientation is difficult in weightless space, and the dynamics of moving around each other are not intuitive. In the field of robotics, issues around effective interactions between the machines and humans, in particular about intentions and actions, usually occur. These problems need to be resolved to leverage the potentialities of the robots.

Feeling Safe Crossing the Road

An increasing issue is understanding the robots in a better way. For instance, Bevilacqua came upon autonomous cars that were being tested on a California road. According to him, there is no way of knowing whether a driverless vehicle will actually stop at the crosswalk. Further, people always rely on cues and eye contact from the driver, but such options may no longer be there over time.

Robots, on their part, are also not able to understand human beings. The author recently read about an autonomous car that was not able to understand a situation where a cyclist balanced himself for a moment without placing his feet down. However, the onboard algorithms were not able to figure out whether the biker was actually staying or going.

When looking at defense and space exploration, similar issues can be seen. For instance, NASA did not tap the full capabilities of its Mars rovers, because the team was not sure what exactly would happen if these rovers were allowed to explore and investigate freely on Mars independently.

Crews of 10 or more trained staff are often used by the Department of Defense to support an airborne unmanned aerial vehicle. However, there is no way of finding out if this drone is really autonomous, whether people are required, or whether people need it. There is also the question of interaction between the humans and machines.

What is “autonomy,” Really?

“Autonomy” refers to “self-governance”, but no man is an island. The same is true for robotic innovations. At present, robots are seen as agents that can operate on their own, like the autonomous vacuum cleaner that still plays a role in the family’s efforts to keep the home clean. Here, communication and the ability to infer intent are the key aspects, if the robots are actually working with us rather than instead of us. While most duties can be done on our own, there is a need to interact with the rest of the team sooner or later.

Humans and autonomous robots are not able to fully understand each other and speak in languages that are foreign to them, and both are yet to learn. However, the question remains how to convey the intent between the robots and humans in both directions, and how to understand and trust the robots. In a similar way, how will the robots learn to trust humans and what cues the other would have for each other?

Trusting and understanding the intentions of humans itself is not an easy task, but still we depend on the known cues, like the eye contact between the driver and the pedestrian at an intersection. As a result, innovative ways have to be developed to read the minds of the robots and vice versa.

A unique display can be given to an astronaut to demonstrate the intentions of the helper spacecraft, just like the gages that are installed in an airplane cockpit and show the status of the plane to the pilot. The displays could even be integrated in to a helmet visor, or improved by sounds that project certain meanings. However, there is no way to find out what data they would convey and how they would know it. Such questions are the basis for innovative work and could provide new avenues to explore the future of inconceivable ideas where robots can redefine our lives.