Jan 13 2016

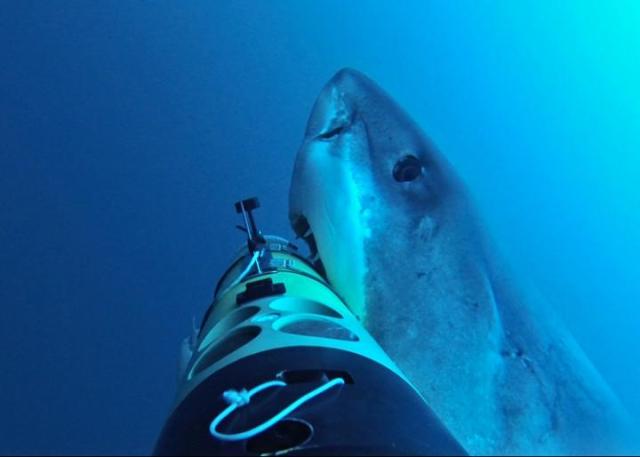

Intense footage of a great white shark attacking the "REMUS Shark Cam" earned the Discovery Channel some of it's highest ratings in Shark Week 2014 and went viral on the internet.

Researchers, including lead author Greg Skomal and the REMUS SharkCam team, logged 30 interactions with 10 individual sharks. The behavior of these sharks ranged from simple approaches to bumping the vehicle and, on nine occasions, aggressive bites. (Credit: Oceanographic Systems Lab/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Researchers, including lead author Greg Skomal and the REMUS SharkCam team, logged 30 interactions with 10 individual sharks. The behavior of these sharks ranged from simple approaches to bumping the vehicle and, on nine occasions, aggressive bites. (Credit: Oceanographic Systems Lab/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

While the footage was extraordinary, the REMUS SharkCam is also providing groundbreaking scientific understanding. In 2013 this autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) was used to monitor white shark behavior, and it represents the first successful attempts to autonomously track and image any animal within the marine environment. Critical data obtained from this research is now being used in efforts to conserve these animals.

We wanted to test the REMUS SharkCam technology to prove that is was a viable tool for observing marine animals--sharks in this case--and to collect substantial data about the animals's behavior and habitat.

Amy Kukulya, WHOI Engineer and REMUS SharkCam's Pricipal Investigator

Results from this research have been published in the Journal of Fish Biology. Greg Skomal, a biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, is the lead author on the paper and, in addition to Kukulya, the other co-authors include WHOI engineer and REMUS SharkCam software developer Roger Stokey, and biologist E. M. Hoyos-Padilla of Pelagios-Kakunjá, a Mexican marine conservation organization.

In November 2013, Kukulya and her team took part in six AUV missions that were conducted over a period of seven days while working in the waters off Mexico's Guadalupe Island. The REMUS SharkCam was used to tag and track four sharks over a period of six days, and more than 13 hours of video data was captured from the AUV. The sharks were tracked down to depths of 100 meters and included three female and one male great white sharks, including the 21-foot Deep Blue.

Most of what we know about white shark predatory behavior comes from surface observations. We have all seen pictures or footage of sharks surging out of the water to capture a sea. But we wanted to find out what was happening at depth--when the sharks swam into the deep, how were these animals behaving? Were they hunting? The REMUS AUV was the perfect tool to do this.

Greg Skomal, Biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries

The team were able to monitor four sharks, though most of the interactions the REMUS SharkCam captured were with animals not being tracked. Thirty encounters with ten separate sharks were logged by the team. The behavior of all these individual sharks ranged from bumping into the vehicle to nine occasions of aggressive bites. The bumps were assumed to represent aggressive behavior consisting of brief physical contact, often with the shark nudging the vehicle with its snout. The bites, which were mostly found at the rear of the vehicle, were considered to be the animal’s predatory behavior.

“Predation events are rarely witnessed," the studies authors wrote. "Virtually all of the published observations of predatory behavior are based on surface interactions." Researchers highlighted that, off Guadalupe, minimum predatory behavior took place in plain sight or at the surface. They also suggest that Guadalupe's clear waters provide varied opportunities for sharks, but were not very helpful in studying the shark's behavior at depth.

The observations made by the team constitute the first observations of predatory behavior well below the surface. The team discovered that the clear waters of Guadalupe enabled sharks to search for seals and to attack them from below, this is where the sharks could hide themselves in the dark water while stalking the seal.

Originally, the REMUS AUV was used for coastal monitoring and mapping, but later versions of the vehicle have been created for a wide range of other activities. The REMUS SharkCam comprises temperature and salinity probes, water current profilers, six HD video cameras, and other sensors in order to help scientists collect a variety of data based on the animals behavior, habitat, and position in the water from many different perspectives and angles.

During the research, Skomal used a harpoon to tag the shark's dorsal fin with a transponder, and Kukulya and Roger Stokey would then immediately activate the REMUS SharkCam. The transponder on the tag allows the AUV to track the shark up to depths of around 100m. After completion of the mission, an acoustic command was sent by the team to the tag's release trigger in order to free the tag from the shark, enabling the tag to float to surface for retrieval.

Recently, the team revisited Guadalupe to continue tagging, filming and studying white sharks. This new footage is scheduled for release in summer 2016 as part of Discovery Channel's Shark Week.

The team hope to use a deeper diving REMUS SharkCam that can swim for a longer duration. Research in the future will thus focus on increasing tracking durations by integrating camera systems into the AUV electronics and using more efficient batteries.

This SharkCam groundbreaking technology offers a new and innovative tool for scientists to better understand the fine-scale behavior of marine animals. There is currently no other method in the world that can get imagery of white sharks at depth in the open ocean. Not only do we get to see what they are doing, but we also know exactly where they are and collect data about the physical environmental in which they live.

Amy Kukulya, WHOI Engineer and REMUS SharkCam's Pricipal Investigator