May 21 2015

Engineers at Virginia Tech have taken the first steps toward building a novel dynamic sonar system inspired by horseshoe bats that could be more efficient and take up less space than current man-made sonar arrays. They are presenting a prototype of their "dynamic biomimetic sonar" at the 169th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America held May 18-22, 2015 in Pittsburgh.

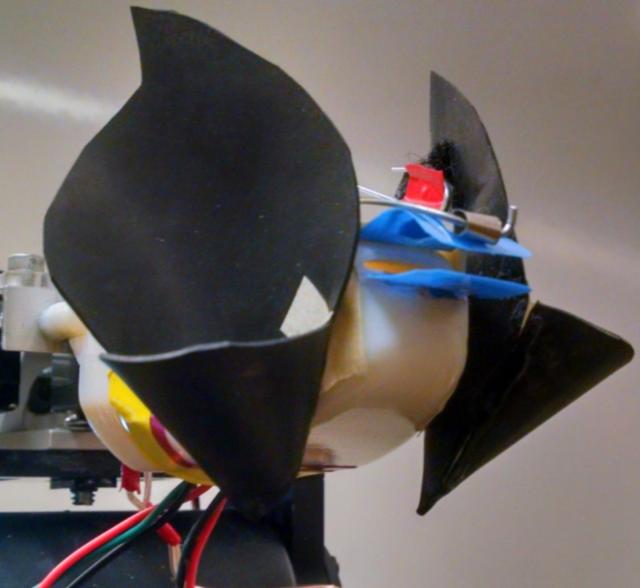

A new robot sonar prototype is inspired by the movable ears and noses that make up the echolocation systems of horseshoe bats. Credit: Philip Caspers/Virginia Tech

A new robot sonar prototype is inspired by the movable ears and noses that make up the echolocation systems of horseshoe bats. Credit: Philip Caspers/Virginia Tech

Bats use biological sonar, called echolocation, to navigate and hunt, and horseshoe bats are especially skilled at using sounds to sense their environment. "Not all bats are equal when it comes to biosonar," said Rolf Müller, a mechanical engineer at Virginia Tech. "Horseshoe bats hunt in very dense forests, and they are able to navigate and capture prey without bumping into anything. In general, they are able to cope with difficult sonar sensing environments much better than we currently can."

To uncover the secrets behind the animal's abilities, Müller and his team studied the ears and noses of bats in the laboratory. Using the same motion-capture technology used in Hollywood films, the team revealed that the bats rapidly deform their outer ear shapes to filter sounds according to frequency and direction and to suit different sensing tasks.

"They can switch between different ear configurations in only a tenth of a second - three times faster than a person can blink their eyes," said Philip Caspers, a graduate student in Müller's lab.

Unlike bat species that employ a less sophisticated sonar system, horseshoe bats emit ultrasound squeaks through their noses rather than their mouths. Using laser-Doppler measurements that detect velocity, the team showed that the noses of horseshoe bats also deform during echolocation-much like a megaphone whose walls are moving as the sound comes out.

The team has now applied the insights they've gathered about horseshoe bat echolocation to develop a robotic sonar system. The team's sonar system incorporates two receiving channels and one emitting channel that are able to replicate some of the key motions in the bat's ears and nose. For comparison, modern naval sonar arrays can have receivers that measure several meters across and many hundreds of separate receiving elements for detecting incoming signals.

By reducing the number of elements in their prototype, the team hopes to create small, efficient sonar systems that use less power and computing resources than current arrays. "Instead of getting one huge signal and letting a supercomputer churn away at it, we want to focus on getting the right signal," Müller said.