Mar 3 2015

How can a humpback whale and a device that works on the same principle as the clicker that starts your gas grill help an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) fly longer and with more stability?

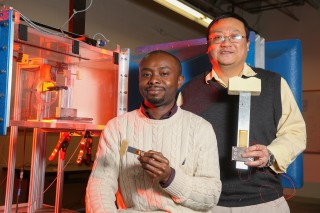

Felix Ewere, left, and Dr. Gang Wang near a wind tunnel they use for testing in UAH’s Olin B. King Technology Hall. Inside the tunnel is their latest miniaturization effort, while Ewere holds the intermediate effort and Dr. Wang holds the initial device constructed. Credit:Michael Mercier / UAH

Felix Ewere, left, and Dr. Gang Wang near a wind tunnel they use for testing in UAH’s Olin B. King Technology Hall. Inside the tunnel is their latest miniaturization effort, while Ewere holds the intermediate effort and Dr. Wang holds the initial device constructed. Credit:Michael Mercier / UAH

Well, it all starts with biological structures called tubercles that the whale uses for its unique maneuvers in the ocean. Felix Ewere, a doctoral student at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), made a mechanical version of the wavy-looking biological structures and attached it to a piezoelectric energy harvester. The piezoelectric principles the harvester uses convert mechanical action into electricity just like the red piezoelectric button on your gas grill does.

Humpback whales have rounded tubercles located on the leading edge of their fins.

“For anything under the action of fluid, two forces are created – a lift force and a drag force,” Ewere says. “For the humpback whale, these tubercles increase the lift and reduce the drag as it moves through the water. They are what enables it to breech the surface of the water.”

Borrowing from the whales, the new device is used to harvest energy and can be employed as an airflow or fluid speed and direction-sensing device. So UAV designers can use the “galloping piezoelectric” principle to design better craft by placing sensor piezoelectric devices all over their models to test them to determine how they behave in the fluid currents of air. Plus, they can attach the devices to the UAV as harvesters to generate power to extend its battery range.

Ewere has a bachelor’s in mechanical engineering and a master’s in aerospace engineering, and for his doctorate he joined his fluid physics experience to the piezoelectric expertise of his doctoral advisor, assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering Dr. Gang Wang.

“He actually introduced me to piezoelectrics,” Ewere says.

The initial problem was to determine whether greater efficiency using wind could be attained so that the piezoelectrics could better harvest energy. Dr. Wang says he presented the problem, but Ewere is the one who came up with an interesting solution that ultimately took the pair in another direction.

“I just threw the question to him, and he found the answer for me, which is using this biologically inspired concept,” Dr. Wang says. “One day, he just knocked on my door and said, ‘Dr. Wang I want to try this one.’ ”

Next came wind tunnel experiments.

“We were trying to get more force and induce more strain by using this idea” to improve energy harvesting ability, Ewere says. It turned out that efficiency wasn’t increased but the pair discovered through experimentation that the devices could serve as a form of passive control. That makes them useful as measuring devices for air flow speed and direction.

“This is a new kind of flow sensor,” Ewere says. “A regular flow sensor will just tell you the magnitude of the wind, but this also shows you the direction.”

Work has progressed on miniaturizing the components to widen applications. Placing the sensors arrays on a helicopter, for example, could help engineers determine aerodynamics that could improve low speed and low altitude flight stability or reduce its acoustic signature.

Its energy harvesting capabilities are also being explored for use to charge the batteries that power small devices to track bird populations, extending their research life.

Now the theoretical work and design concept phases are drawing to a close and Dr. Wang is looking for applications funding.

“For three or four years now, we have been drawing up the basics of this, and we have done the basic research,” Dr. Wang says. “Now I have the tangible benefits for it, but to take it to the next level I need a boost from an interested funding agency.”