Nov 17 2014

A cat always lands on its feet. At least, that’s how the adage goes. Karen Liu hopes that in the future, this will be true of robots as well.

To understand the way feline or human behavior during falls might be applied to robot landings, Liu, an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing (IC) at Georgia Tech, delved into the physics of everything from falling cats to the mid-air orientation of divers and astronauts.

In research presented at the 2014 IEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Liu shared her studies of mid-air orientation and impact behavior in both cats and humans as it applies to reduced impact in falling robots, especially those that one day may be used for search-and-rescue missions in hazardous conditions.

Not only did Liu and her team of Georgia Tech researchers simulate falls, they also studied the impact of landings.

“It’s not the fall that kills you. It’s the sudden stop at the end,” Liu said. “One of the most important factors that determines the damage of the fall is the landing angle.”

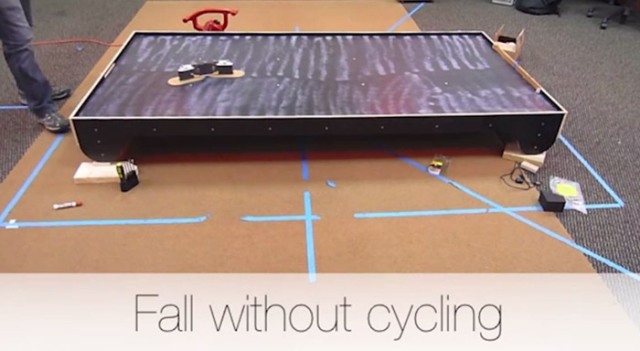

In their experiments with a small robot consisting of a main body and two symmetric legs with paddles, the team compensated for the fact that a robot cannot move fast enough in a laboratory setting by creating a reduced-gravity environment using a tilted surface similar to an air hockey table outfitted with a leaf blower. Liu along with Jeffrey Bingham, Ravi Haksar, Jeongseok Lee and Jun Ueda, simulated the elements of a long fall and explored the possibility of a “soft roll” landing to reduce impact and damage to the robot.

In their work, the researchers found that a well-designed robot has the “brain” to process the computation necessary to achieve a softer landing, though current motor and servo technology does not allow the hardware to move quickly enough for cat-like impacts. Future research aims at further teaching a robot the skill of orientation and impact, a feat that falling humans cannot achieve but cats perform naturally.

“Most importantly, the human brain cannot compute fast enough to determine the optimal sequence of poses the body needs to reach during a long-distance fall to achieve a safe landing,” the researchers note.

“Theoretically, no matter what initial position and initial speed we have, we can precisely control the landing angle by changing our body poses in the air,” says Ueda, an associate professor in the Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “In practice, however, we have a lot of constraints, like joint limits or muscle strength, that prevent us from changing poses fast enough.”

“If we believe that one day we will have the capability to build robots that can do this kind of highly dynamic motion, we also have to teach robots how to fall — and how to land, safely, from a jump or a relatively high fall,” Liu said.

Learn how to teach robots to fall in the College of Computing’s “Cats and Athletes Teaching Robots to Fall” research video.

Cats and Athletes Teach Robots to Fall

For more of Liu’s research, visit “Falling and Landing Motion Control for Character Animation.” For the research paper, go to “Orienting in Mid-air through Configuration Changes to Achieve a Rolling Landing for Reducing Impact after a Fall.”

This research is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Award EFRI-1137229 and by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Award HR0011-12-C-0111. Any conclusions or opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF or DARPA.