Aug 17 2020

While humans often use more than one sense to comprehend the world, robots predominantly depend on vision and, increasingly, touch sensations.

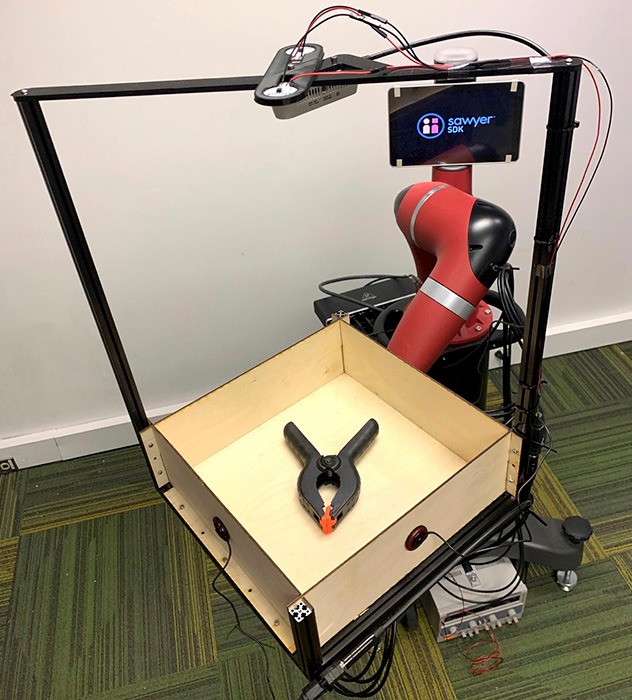

To prove that sound can be an asset to robots, SCS researchers built a dataset by recording video and audio of 60 common objects as they rolled around a tray. The team captured these interactions using Tilt-Bot—a square tray attached to the arm of a Sawyer robot. Image Credit: Carnegie Mellon University.

To prove that sound can be an asset to robots, SCS researchers built a dataset by recording video and audio of 60 common objects as they rolled around a tray. The team captured these interactions using Tilt-Bot—a square tray attached to the arm of a Sawyer robot. Image Credit: Carnegie Mellon University.

According to scientists from Carnegie Mellon University, adding another sense—that is, hearing—could significantly enhance the perception of a robot.

In the so-called first large-scale study of the communications between robotic action and sound, scientists from the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University discovered that sounds can possibly help robots distinguish between objects such as a metal wrench and a metal screwdriver.

In addition, hearing could help robots find out the type of action that creates a sound and help them utilize sounds to estimate the physical characteristics of novel objects.

A lot of preliminary work in other fields indicated that sound could be useful, but it wasn’t clear how useful it would be in robotics.

Lerrel Pinto, PhD in Robotics, Carnegie Mellon University

Pinto will shortly join the faculty of New York University in fall 2020.

Together with his collaborators, Pinto determined that the performance rate was very high in the case of robots that apply sound, effectively categorizing objects 76% of the time.

According to Pinto, such encouraging outcomes may prove handy to equip upcoming robots with instrumented canes, allowing them to tap on objects they want to detect.

The team presented the study results in July 2020 during the virtual Robotics Science and Systems conference. Other members of the team included Abhinav Gupta, an associate professor of robotics, and Dhiraj Gandhi, a former master’s student who is currently a research engineer at Pittsburgh laboratory of Facebook Artificial Intelligence Research.

To carry out the research, the team generated a huge dataset and concurrently recorded audio and video of a total of 60 common objects—such as shoes, hand tools, apples, tennis balls, and toy blocks—as they rolled or slid near a tray and collapsed into its sides. Since the release of this dataset, the researchers have cataloged a total of 15,000 interactions for use by other scientists.

To record such interactions, the team used an experimental apparatus which they dubbed Tilt-Bot—a square tray fixed to the arm of a Sawyer robot. This method was efficient to construct a huge dataset; the team could position an object in the tray and allow the Sawyer robot to spend some hours shifting the tray in arbitrary directions with different levels of tilt as microphones and cameras recorded every action.

The team also gathered some amount of data that was beyond the tray, by using the Sawyer robot to push objects on a surface.

Although this dataset has an unparalleled size, other scientists have also investigated how smart agents can gain data by using only sound. For example, Oliver Kroemer, an assistant professor of robotics, headed a study in which sound was used to predict the number of granular materials such as pasta or rice, predicting the flow of these materials from a scoop, or by shaking a container.

According to Pinto, the usefulness of sound for robots was hence not unexpected, although he and the other researchers were stunned at just how handy it proved to be. For example, they observed that a robot could apply what it learned about the sound of a single set of objects to make estimations regarding the physical characteristics of earlier unseen objects.

I think what was really exciting was that when it failed, it would fail on things you expect it to fail on.

Lerrel Pinto, PhD in Robotics, Carnegie Mellon University

For example, a robot could not use sound to tell the difference between a green block or a red block. “But if it was a different object, such as a block versus a cup, it could figure that out,” added Pinto.

The study was funded by the defense advanced research projects agency and the office of naval research.

Tilt-Bot in Action

Video Credit: Carnegie Mellon University.