Apr 10 2020

A new technique developed by engineers from the University of California San Diego avoids the need for any exclusive equipment and creates flexible, soft, 3D-printed robots in just minutes.

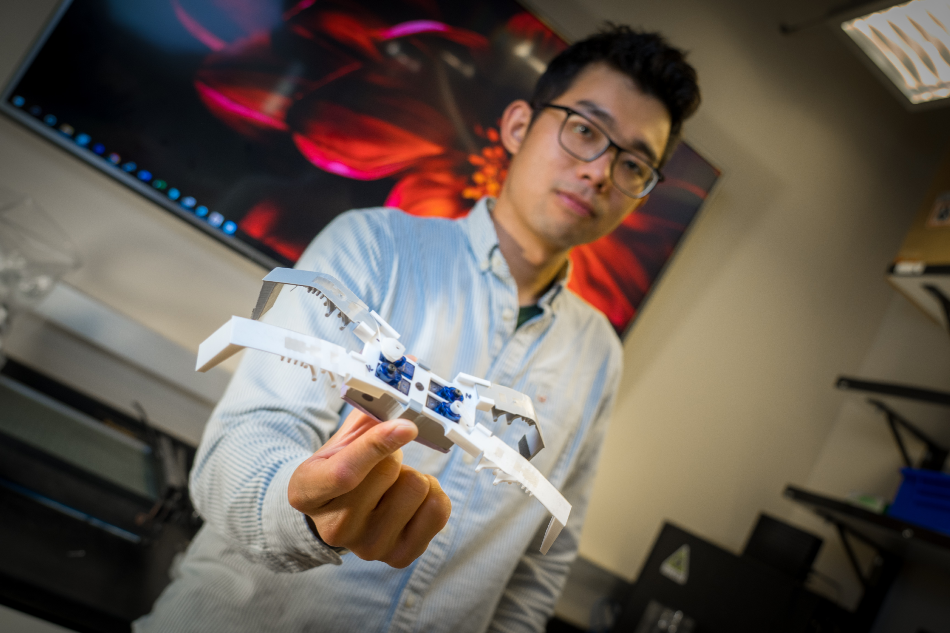

Ph.D. student James Jiang, the paper’s first author, shows one of the flexoskeletons developed with the researchers’ 3D printing method. Image Credit: University of California San Diego.

Ph.D. student James Jiang, the paper’s first author, shows one of the flexoskeletons developed with the researchers’ 3D printing method. Image Credit: University of California San Diego.

The invention arises from re-evaluating how soft robots are developed: rather than finding out how to add soft materials to a rigid robot body, researchers at UC San Diego began working with a soft body and added rigid features to main components. Since the structures were inspired by the exoskeletons of insects—that include both soft and rigid parts—the researchers named their robots “flexoskeletons.”

The new technique enables developing soft components for robots in a fraction of the time earlier required and for only a fraction of the cost.

We hope that these flexoskeletons will lead to the creation of a new class of soft, bioinspired robots. We want to make soft robots easier to build for researchers all over the world."

Nick Gravish, Study Senior Author and Mechanical Engineering Professor, Jacobs School of Engineering, UC San Diego

The new technique enables developing large groups of flexoskeleton robots with very less manual assembly. It also allows the assembly of a library of Lego-like components to facilitate easily swapping of robot parts.

The flexoskeletons are made by 3D printing a rigid material on a thin sheet that serves as a flexible base. Several features are added while printing the flexoskeletons, thereby increasing the rigidity in certain areas, which is again inspired by insect exoskeletons that integrate rigidity and softness for support and movement.

The study findings have been reported in the April 7th issue of the Soft Robotics journal. The researchers hope to make their designs accessible to scientists at other institutions and even high schools.

It takes 10 minutes to print a single flexoskeleton component that costs less than $1. Printing of flexoskeletons can be performed on a majority of the less expensive printers available in the market. Less than 2 hours is needed to print and assemble a complete robot.

The team analyzed an array of materials until the suitable flexible surface was found to print the flexoskeletons, which turned out to be a polycarbonate sheet. Careful examination of the behavior of insects helped them add features to enhance rigidity.

The ultimate aim is to develop an assembly line that prints complete flexoskeleton robots without requiring hand assembly. A group of these tiny robots could work as much as one huge robot on its own, or even more.

In 1989, Rodney Brooks, cofounder iRobot who was then working at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab, proposed space missions that would include “large numbers of mass-produced simple autonomous robots that are small by today’s standards.”

He and co-author Anita Flynn named the paper “Fast, cheap and out of control: a robot invasion of the solar system.” For Gravish, the paper was seminal and he believes this study is a step forward in that direction, however for the field of robotics as a whole, not just for space.