Sep 27 2019

Why do antidepressants benefit only certain people? The psychiatry field has been looking for answers to explain this mystery for a long time.

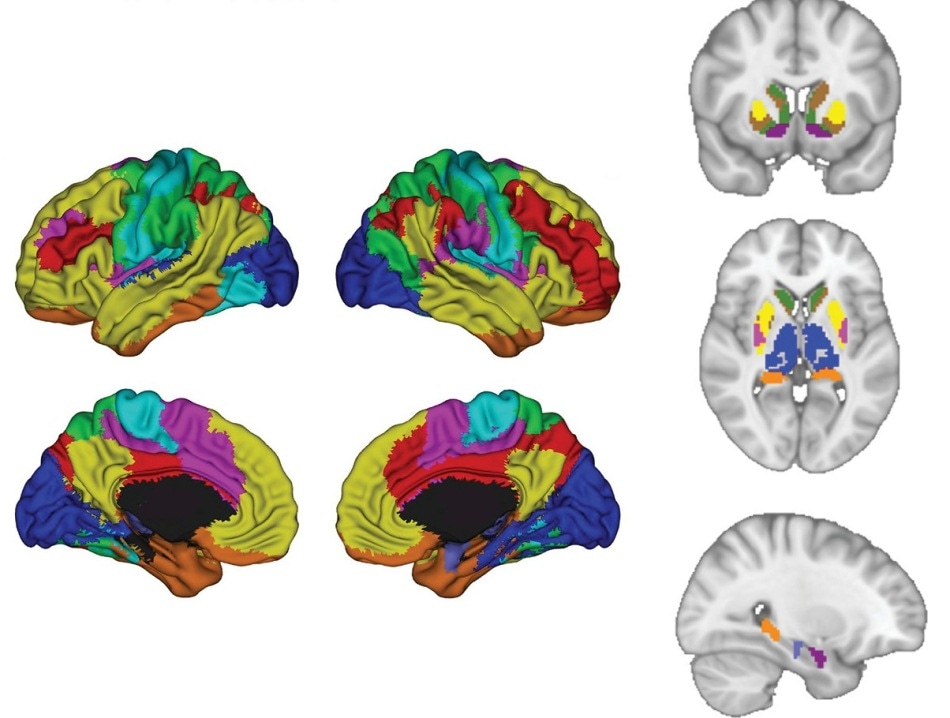

Scientists used artificial intelligence to examine neural activity throughout the brain while study participants processed emotions. (Image credit: UT Southwestern Medical Center)

Scientists used artificial intelligence to examine neural activity throughout the brain while study participants processed emotions. (Image credit: UT Southwestern Medical Center)

It is not known if a patient’s recovery is simply tied to the placebo effect—that is, the self-fulfilling belief that a therapy will be effective—or if the person’s biology influences the outcome.

UT Southwestern Medical Center is heading two studies that offer proof about the effect of biology. Here, artificial intelligence (AI) was used to detect brain activity patterns that make people less reactive to specific antidepressants. In other words, researchers demonstrated that by imaging a patient’s brain, conclusions can be reached regarding the efficacy of the drug.

The two studies include recent findings from an extensive national trial (EMBARC). The trial was meant to establish objective, biology-based methods to cure mood disorders and reduce the trial and error of the proposed treatments. If this proves effective, researchers believe that this would enable the use of a series of tests like blood analyses and brain imaging to improve the chances of identifying the most optimized treatment.

We need to end the guessing game and find objective measures for prescribing interventions that will work. People with depression already suffer from hopelessness, and the problem can become worse if they take a medication that is ineffective.

Dr Madhukar Trivedi, Founding Director, Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Dr Trivedi also oversees the EMBARC trial.

Brain Activity

Over 300 participants are included in each study in which imaging was used to assess brain activity both during the processing of emotions and in a resting state. In both the studies, the participants were divided into two groups—people with depression who either received a placebo or antidepressants, and a healthy control group.

Among the study participants who received the drug, correlations were found between the way brain is wired and whether a participant’s condition is likely to improve within a couple of months of taking an antidepressant drug.

According to Dr Trivedi, imaging various states of the brain’s activity was crucial to obtain a more precise idea of how depression manifests in a specific patient. He added that for certain people, the more pertinent data can be obtained from their brains’ resting state. In others, the emotional processing will be a significant part and can predict more accurately whether or not an antidepressant drug will work.

Depression is a complex disease that affects people in different ways. Much like technology can identify us through fingerprints and facial scans, these studies show we can use imaging to identify specific signatures of depression in people.

Dr Madhukar Trivedi, Founding Director, Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Improving Outcomes

Data from the two studies was obtained from the 16-week EMBARC trial, which was initiated by Dr Trivedi in 2012 at four sites in the United States.

As part of the project, patients with major depressive disorder were assessed via brain imaging and numerous blood, DNA, and other types of tests. Dr Trivedi’s aim was to tackle a disconcerting finding from another study (STAR*D), which was headed by him. In this study, around two-thirds of patients did not sufficiently respond to their first antidepressant medication.

Published in 2018, EMBARC’s initial study focused on how the brain’s electrical activity can indicate if a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is likely to benefit a patient. SSRI is the most common class of antidepressant.

This discovery has been followed by an associated study that detects other predictive tests for SSRIs; the resting-state brain imaging study was recently reported in the American Journal of Psychiatry, and the second imaging study was reported in Nature Human Behaviour.

AI and Depression

The research published in Nature employed AI to establish connections between the effectiveness of an antidepressant drug and the way emotional conflict is processed by a patient’s brain.

Study participants subjected to brain imaging were shown pictures in rapid succession that provided at times conflicting messages like an angry face depicting the word “happy,” or the other way round.

All the participants were asked to read the word provided on the photograph and then click on the subsequent image. But instead of observing only neural regions that are assumed to be applicable to predict the benefits of antidepressants, researchers utilized machine learning to examine the entire brain activity.

“Our hypotheses for where to look have not panned out, so we wanted to try something different,” added Dr Trivedi.

AI was able to identify certain brain regions—for instance, in the lateral prefrontal cortices—that were most crucial for predicting whether an SSRI would benefit the participants. The outcomes revealed that participants who experienced abnormal neural responses at the time of emotional conflict have fewer chances to improve within a period of eight weeks of initiating the drug.

Ongoing Research

Dr Trivedi has also started other major research projects to gain a deeper understanding of the underpinnings of mood disorders. A D2K study is one of the projects that would recruit 2,500 patients suffering from bipolar disorders and depression and track them for two decades. Moreover, RAD is a decade-old study involving 2,500 participants (aged 10–24) and will expose factors for minimizing the risk of developing anxiety or mood disorders.

Making use of these enrollees, the research group of Dr Trivedi will examine the outcomes from a number of other tests to boost brain imaging. This would also allow the team to evaluate the biological signatures of patients more accurately and thus establish the most optimized treatment.

Dr Trivedi has had initial success in designing a blood test but admits that only patients with a certain type of inflammation would benefit from this.

According to him, integrating blood and brain tests will improve the possibilities of selecting the right therapy the first time.

We need to look at this issue in several ways to identify the many different signatures of depression in the body. The findings from these new studies are significant and bring us closer to using them clinically to improve outcomes for millions of people.

Dr Madhukar Trivedi, Founding Director, Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care, UT Southwestern Medical Center