Aug 21 2019

A few summers ago, a huge number of people started using the Pokemon Go app to obtain virtual creatures that were hiding themselves in the physical world.

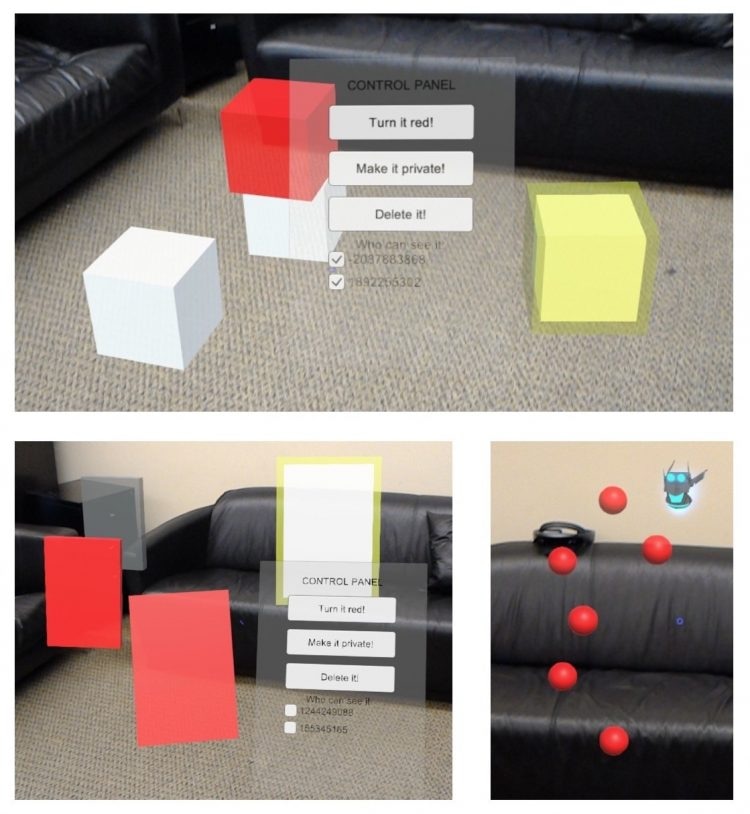

(Image credit: Ruth et al./USENIX Security Symposium)

(Image credit: Ruth et al./USENIX Security Symposium)

This app was regarded as the first-ever mass-market augmented reality (AR) game, and now AR is largely viewed as a solo activity.

However, people may soon be utilizing this technology for a wide range of group activities, like collaborating on creative or work projects or playing multi-user games. Conversely, it is difficult for app developers to protect against bad actors who attempt to steal these experiences, and simultaneously prevent privacy breaches in environments spanning physical and digital space.

To resolve this problem, security researchers at the University of Washington have developed a new toolkit called ShareAR that allows app developers to build in interactive and collaborative features without compromising on the security and privacy of their users.

The scientists presented their latest findings at the USENIX Security Symposium in Santa Clara, California on August 14th, 2019.

A key role for computer security and privacy research is to anticipate and address future risks in emerging technologies. It is becoming clear that multi-user AR has a lot of potential, but there has not been a systematic approach to addressing the possible security and privacy issues that will arise.

Franziska Roesner, Study Co-Author and Assistant Professor, Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington

Sharing virtual objects in AR technologies can be—to a certain extent—compared to sharing files on a cloud-based platform such as Google Drive, but there is a huge difference.

“AR content isn’t confined to a screen like a Google Doc is. It’s embedded into the physical world you see around you,” stated first author Kimberly Ruth, a UW undergraduate student in the Allen School. “That means there are security and privacy considerations that are unique to AR.”

For instance, people may scribble virtual offensive messages on places of worship, add virtual unfitting images to physical public parks, or even fix a virtual “kick me” sign on the back of an unsuspecting user.

“We wanted to think about how the technology should respond when a person tries to harass or spy on others, or tries to steal or vandalize other users’ AR content,” Ruth stated. “But we also don’t want to shut down the positive aspects of being able to share content using AR technologies, and we don’t want to force developers to choose between functionality and security.”

Therefore, to deal with these problems, the researchers developed ShareAR—a prototype toolkit for the Microsoft HoloLens. Through this toolkit, applications can generate, share, and monitor objects that users share with one another.

There is another possible problem with multi-user AR: Developers require a method to signal the physical location of a person’s private virtual content to prevent other users from inadvertently standing in between that person and his or her work; this is similar to standing between the TV and someone. Therefore, the researchers created “ghost objects” for the ShareAR toolkit.

A ghost object serves as a placeholder for another virtual object. It has the same physical location and rough 3D bulk as the object it stands in for, but it doesn’t show any of the sensitive information that the original object contains.

Kimberly Ruth, Study First Author and Undergraduate Student, Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington

Ruth continued, “The benefit of this approach over putting up a virtual wall is that, if I’m interacting with a virtual private messaging window, another person in the room can’t sneak up behind me and peer over my shoulder to see what I’m typing—they always see the same placeholder from any angle.”

The researchers tested the new toolkit with three case study apps. The most computationally costly actions involved producing objects and modifying permission settings within the apps.

However, even when the team attempted to stress out the system with massive numbers of shared objects and users, the toolkit took just 5 ms to conclude a task. It took relatively less in a majority of the cases, that is, less than 1 ms.

The ShareAR App can now be downloaded by developers for use in their own HoloLens apps.

“We’ll be very interested in hearing feedback from developers on what’s working well for them and what they’d like to see improved,” Ruth stated. “We believe that engaging with technology builders while AR is still in development is the key to tackling these security and privacy challenges before they become widespread.”

The co-author of the paper is Tadayoshi Kohno, a professor in the Allen School. The National Science Foundation and the Washington Research Foundation funded the study.