Aug 14 2019

According to a new eLife study, a new automated tool that can track the movement of particles within cells could speed up research in several fields.

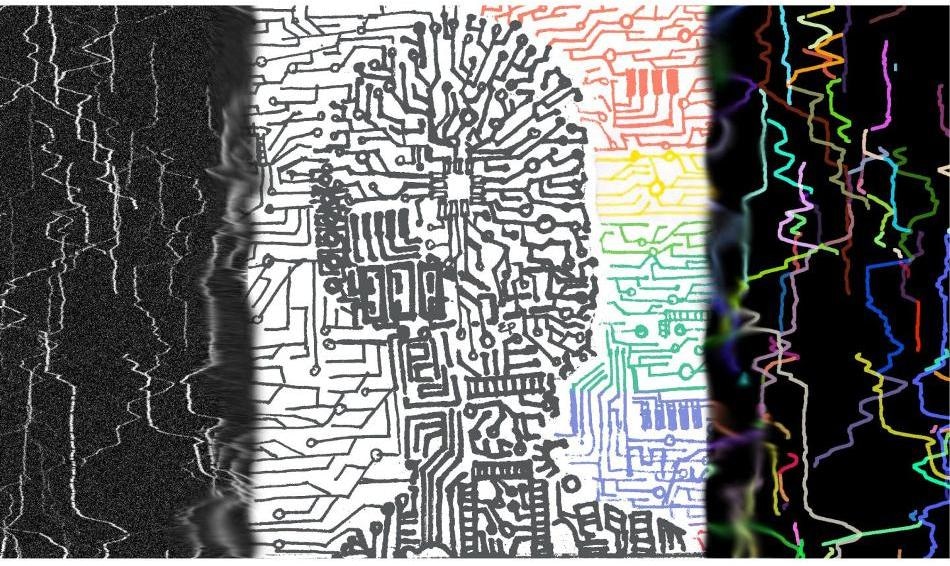

Beyond manual tracing: An artist’s impression of a deep neural network trained to recognize particle motion in space-time representations. (Image Credit: Eva Pillai)

Beyond manual tracing: An artist’s impression of a deep neural network trained to recognize particle motion in space-time representations. (Image Credit: Eva Pillai)

The movements of proteins, small molecules, and cellular constituents across the body play a key role in health and disease. For instance, they support brain development and the progression of certain diseases. The new tool, developed with advanced machine learning technology, will enable these movements to be mapped more quickly, easily, and less prone to bias.

At present, researchers may use images known as kymographs, which represent the movement of particles in time and space, for examining particle movements. The kymographs are derived from time-lapse videos of particle movements recorded with the help of microscopes. The analysis must be carried out manually, which is slow as well as prone to unconscious biases of the scientist.

We used the power of machine learning to solve this long-standing problem by automating the tracing of kymographs.

Maximilian Jakobs, Study Lead Author and PhD student, Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge

To automate the process, the group created the software called “KymoButler.” The software employs deep learning technology, which attempts to imitate the networks in the brain to enable the software to learn and turn more proficient at a task in due course and multiple attempts. They subsequently tested KymoButler using both real and artificial data from researchers analyzing the movement of an array of different particles.

“We demonstrate that KymoButler performs as well as expert manual data analysis on kymographs with complex particle trajectories from a variety of biological systems,” Jakobs explains. The software could also finish analyses in less than a minute that would normally take 1.5 hours for an expert.

KymoButler is available for other scientists to download and use at kymobutler.deepmirror.ai. Senior author Kristian Franze, Reader in Neuronal Mechanics at the University of Cambridge, hopes that the software will continue to advance as it analyzes more varieties of data.

Scientists who use the tool will be offered the option to anonymously upload their kymographs to help the group continue developing the software.

“We hope our tool will prove useful for others involved in analyzing small particle movements, whichever field they may work in,” stated Franze, whose lab is committed to gaining insights on how physical interactions between cells and their environment mold the development and regeneration of the brain.