May 8 2019

Although there have been significant advances in modern imaging and genetics, a majority of the breast cancer patients are caught by surprise during diagnosis. For some, it is revealed too late.

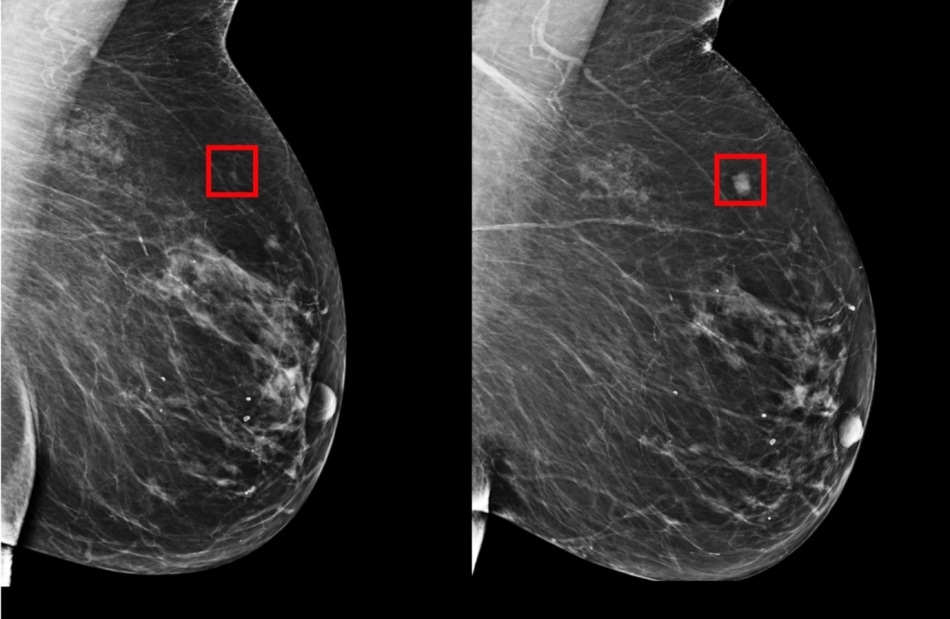

The team’s model was shown to be able to identify a woman at high risk of breast cancer four years (left) before it developed (right). (Image credit: Courtesy of the researchers)

The team’s model was shown to be able to identify a woman at high risk of breast cancer four years (left) before it developed (right). (Image credit: Courtesy of the researchers)

Delayed diagnosis implies vigorous treatments, outcomes that are unreliable, and higher medical expenses. Consequently, it has been a mainstay to identify patients in breast cancer research and effective early detection.

Bearing this in mind, a group from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has developed an innovative deep-learning model with the ability to predict from a mammogram whether a patient has chances of developing breast cancer nearly five years in the future. The model has been trained on mammograms and known outcomes from more than 60,000 MGH patients and has learned the delicate patterns in breast tissue that are precursors to malignant tumors.

According to Regina Barzilay, an MIT Professor who is a breast cancer survivor herself, the expectation is for systems such as these to empower doctors to personalize screening and prevention programs at the individual level, rendering delayed diagnosis an artifact of the past.

Despite that mammography has been demonstrated to minimize breast cancer mortality, the debate on when to start and how often to screen is still ongoing. The American Cancer Society recommends annual screening beginning at the age of 45, whereas the U.S. Preventative Task Force suggests screening every two years beginning at the age of 50.

Rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach, we can personalize screening around a woman’s risk of developing cancer. For example, a doctor might recommend that one group of women get a mammogram every other year, while another higher-risk group might get supplemental MRI screening.

Regina Barzilay, Delta Electronics Professor, CSAIL; Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT

Barzilay, who is also a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, is the senior author of a new paper related to the project published in Radiology on May 7th, 2019.

Compared to the prevalent approaches, the new model was considerably better at predicting risk: It was accurate in placing 31% of all cancer patients in its highest-risk category, than only 18% achieved by conventional models.

According to Harvard Professor Constance Lehman, previously, there has been very little support in the medical community for screening approaches that are risk-based and not age-based.

This is because before we did not have accurate risk assessment tools that worked for individual women. Our work is the first to show that it’s possible.

Constance Lehman, Professor of Radiology, Harvard Medical School

Lehman is also the division chief of breast imaging at MGH.

Barzilay and Lehman were the co-authors of the paper and Adam Yala, a CSAIL PhD student, was the lead author. Other MIT co-authors include PhD student Tal Schuster and former master’s student Tally Portnoi.

How it Works

From the time the first breast-cancer risk model was developed in 1989, advancement has mainly been driven by human intuition and knowledge of what could be the major risk factors, for example, age, hormonal and reproductive factors, family history of breast and ovarian cancer, and breast density.

But a majority of these markers only have a weak correlation with breast cancer. Consequently, models such as these still are not so accurate at the individual level, and several organizations still feel that risk-based screening programs are not feasible, due to these limitations.

Instead of manually identification of the patterns in a mammogram that drive future cancer, the MIT/MGH group trained a deep-learning model to derive the patterns directly from the data. The model used information from over 90,000 mammograms and detected patterns too fine for the human eye to detect.

Since the 1960s radiologists have noticed that women have unique and widely variable patterns of breast tissue visible on the mammogram. These patterns can represent the influence of genetics, hormones, pregnancy, lactation, diet, weight loss, and weight gain. We can now leverage this detailed information to be more precise in our risk assessment at the individual level.

Constance Lehman, Professor of Radiology, Harvard Medical School

Making Cancer Detection More Equitable

The study also intends to make risk assessment even more accurate specifically for racial minorities. A number of early models were created on white populations and were considerably less accurate for other races.

Meanwhile, the MIT/MGH model is equally accurate for black and white women. This is specifically important since black women have been shown to be 42% more likely to die from breast cancer due to an extensive range of factors such as differences in detection and access to health care.

It’s particularly striking that the model performs equally as well for white and black people, which has not been the case with prior tools. If validated and made available for widespread use, this could really improve on our current strategies to estimate risk.

Allison Kurian, Associate Professor of Medicine and Health Research/Policy, Stanford University School of Medicine

According to Barzilay, their model could also someday allow doctors to use mammograms to check whether patients are at an elevated risk of other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease or other cancers. The scientists are looking forward to using the models to other ailments and diseases, and specifically those with less effective risk models, such as pancreatic cancer.

“Our goal is to make these advancements a part of the standard of care,” stated Yala. “By predicting who will develop cancer in the future, we can hopefully save lives and catch cancer before symptoms ever arise.”